“The Bible Says” or “Paul Says”? A Response to Andy Stanley

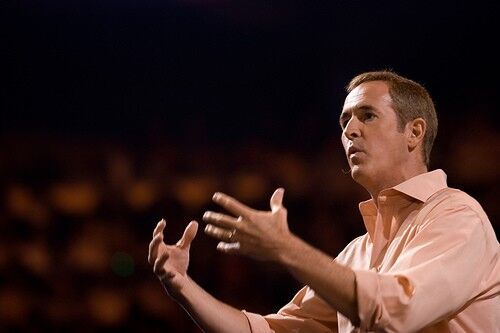

Andy Stanley gave a talk last week at Exponential, a church planting conference in Florida, under the theme of “rethinking preaching.” Stanley is a powerful communicator, and his message stimulated a lot of thinking.

I want to summarize Stanley’s message as accurately as possible, and then evaluate the strengths of his approach, as well as some of my concerns.

Quote Authors, Not the Bible

Stanley’s aim is to preach to unchurched people with the right approach. He is concerned that we often assume a lot in our preaching, leaving the bottom rungs off the ladder. He affirms his belief in Scripture as God’s authoritative Word.

Because unchurched people do not recognize the authority of Scripture, however, Stanley advises preachers to avoid saying, “The Bible says…” Instead, we should quote authors. For instance, “James, the brother of Jesus, writes…” “Paul, who hated Christians and yet became one, writes…” People who will not immediately concede the authority of Scripture will be led to consider the stories of the authors who wrote Scripture, and that background will make the content more compelling.

Why take this approach? “The problem with ‘The Bible says’ is what else the Bible says,” says Stanley. The unchurched will ask why we should trust one section of Scripture when other Scriptures contain truths that are hard to swallow, and that require some explanation. As well, Stanley argues that the foundation of our faith is not the Bible, but an event: the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus. The Bible is not a single book in any case, but a collection of books.

Stanley is not disputing the authority of Scripture. He is simply saying that it is important to understand that an unchurched audience does not share this conviction. We can appeal to the authors and their stories in order to build common ground with the unchurched, which can lead to a recognition of Scripture’s authority. For instance, we can use Jesus’ view of the Hebrew Scriptures to build a case of the the authority of Hebrew Scripture.

(Another attendee has blogged his notes from Stanley’s talk. It contains a few other points I’m not mentioning here.)

Strengths of Stanley’s Proposal

There’s a lot to like about Stanley’s suggestion. We can’t assume that our audiences accept the authority of Scripture. We should be making a case for why people should listen to the text. It can be very effective to root texts in the larger story of how God worked in the lives of the authors so that they wrote what they did. And, in the end, it’s important to remember that effective preaching includes apologetics.

Some Cautions

While Stanley’s approach has a lot to commend it, I do have three cautions and concerns.

I want to expect more of the audience. I could be wrong, but I’m not sure Stanley’s proposal gives enough credit to the audience. We may say we are simply quoting Paul or James, but our listeners will still realize we are quoting from the Bible, and they will still bring their questions about some of the more difficult passages of Scripture. I have no problem with quoting authors; I’m just not sure that people will think I’m not quoting the Bible. In fact, I want them to think I’m quoting the Bible. My assumption is that we can preach in a way that doesn’t sidestep that we are quoting Scripture, even as we build the case for why we need to recognize its authority.

I want to expect more of Scripture. The reason Scripture is authoritative is not because of the authors and their stories. The reason Scripture is authoritative is because God has spoken and revealed himself. There are times to defend and establish the authority of Scripture; there are also times to unleash Scripture and let it do its work, realizing the Holy Spirit is in the room. When God speaks, something happens, even if the hearer doesn’t recognize that it’s God who is speaking.

I want to guard against losing confidence in Scripture. I am not saying that Stanley does this; quite the opposite. I am concerned, however, that those who take his advice seriously may find that it can lead to a subtle shift. It may lead to conceding some of the authority that belongs to Scripture, and giving it to the audience instead. We don’t stand in judgment of Scripture; Scripture stands in judgment of us. I want to keep this clear in my mind, even as I use apologetics to make the case for why we need to hear God’s Word.

To use an illustration: when a judge renders a verdict we don’t like, the judge’s personal story isn’t ultimately the reason why his or her verdict stands. When the judge speaks, the law speaks with all its weight. When Scripture speaks, the personal backgrounds of the authors may be fascinating, but it’s ultimately compelling and authoritative because God has spoken, and the words carry his weight.

Parenthetically: The church in North America faces a lot of challenges. In my opinion, an over-confidence in Scripture is probably not one of them. My impulse is to move toward a greater reliance on Scripture and its authority. Stanley’s proposal may be targeting a problem that doesn’t exist to the extent that I wish it did.

Stanley loves Scripture, and is clearly a good communicator, and his suggestion has a lot going for it. But I never want to let the listeners escape having to wrestle with the fact that God, not just Paul or James, has spoken, and that we need to listen. We can quote the authors, but let’s never be afraid to say, “The Bible says…”